Andy Lin is a National Geographic Traveler award-winning photographer and the creative director of The Self-Portrait Project, a visual art and archive endeavor. Since 2009, The Self-Portrait Project has been empowering people in the creation of their own images utilizing a two-way mirror and remote control. Andy is also a co-founder of Other Worlds, a multi-media non-profit that sought to document and disseminate cases of alternative economies around the world. He is an accomplished speaker on international social change, youth philanthropy, and alternative economies, and has addressed audiences at the University of Berkeley Law School, Dartmouth College, and the U.S. Social Forum. Andy is a former assistant to photographers Raymond Patrick, Ellinor Stigle, Gray Scott, and Richard Phibbs.

We spoke with Andy to learn more about his career path, how he’s using photography to drive social change, and what projects he’s tackling next.

Hi Andy! Tell us a little about yourself — when did you first become interested in photography and how did you get to where you are today?

My earliest memory of photography is finding my father’s Kodak Instamatic in a drawer when I was 8 and using it on a school field trip to the zoo. Growing up, I loved the outdoors and wanted to be Ansel Adams or Galen Rowell.

I took photography classes in high school and college, shot for school newspapers and yearbooks, took odd jobs shooting events and taking headshots, and later after I’d moved to New York, assisted travel, portrait, and fashion photographers. I originally moved to the city to play music, and always took photos out of a love for taking photos, but when the band I was in broke up I saw the event as an opening to pursue photography in a more intentional manner.

In 2006 I co-founded a non-profit, Other Worlds, for which I documented alternative economies around the globe; three years later, inspired by some of those same economies, I created The Self-Portrait Project (SPP), which has become my life’s work.

How did you get into philanthropy and utilizing photography for social change?

My father died in the most devastating accidental air disaster in U.S. history, the 1979 crash of American Airlines Flight 191 at Chicago O’Hare. As a result of my family’s successful court case against the plane’s manufacturer, I came into a sizable amount of money when I became an adult. I was fortunate to connect to progressive philanthropic organizations which helped me to not only develop my understanding of social change, but also to focus my giving, groups like the Center for Economic Justice, Grantmakers without Borders, and Resource Generation.

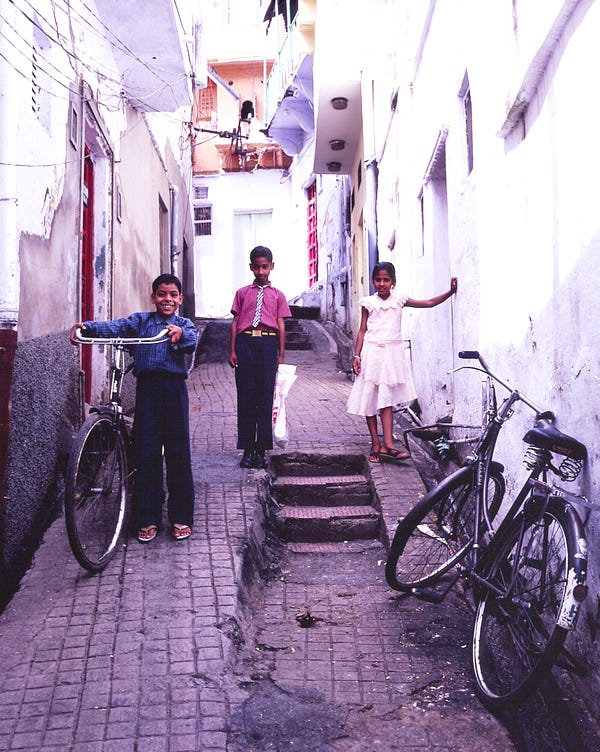

I embarked on a philanthropic + photographic learning tour of sorts to India in 2003, meeting with activists and NGOs across the subcontinent to glean what was wrong in the world and how I as a funder might help support those working to make things right, and documenting the people and places I encountered along the way with my camera. Looking back, I now understand the trip was a vision quest of sorts; I was discovering social change, deepening my eye, and fleshing out my life’s purpose, which combines these two things.

Shortly after I returned from India, I won 3rd prize in National Geographic Traveler magazine’s annual photo contest for a portrait I took of a freed bonded slave laborer painting outside of Mumbai. The prize gave me confidence in my skills as a photographer and helped reinforce my path, which brought me to social justice activist and author Beverly Bell, with whom I founded Other Worlds.

Can you tell us more about Other Worlds? What inspired you to create this non-profit?

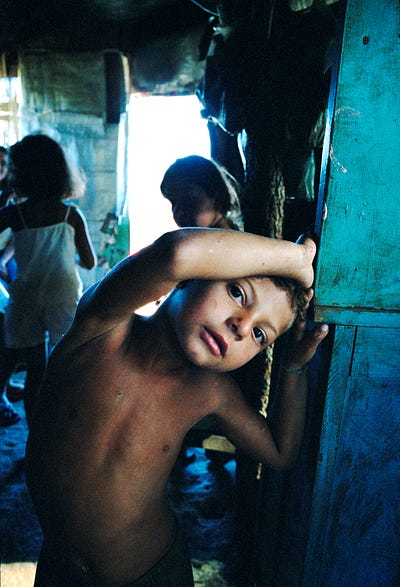

Other Worlds was a multi-media non-profit that was founded in order to inspire hope that just alternatives exist to the profits-over-people paradigm so prevalent in the world. In the early 2000’s I was going on international philanthropic trips and coming back to New York inspired by the changemakers I met but unable to adequately express that hope to my community. I met Beverly Bell on one such trip, and we soon saw that we shared a common goal and had complementary talents — she as a writer and I as a photographer. Along with Gustavo Castro Soto, a Mexican organizer and ally to the indigenous-led Zapatistas in Chiapas, we founded Other Worlds in 2006. During my time with the organization, I traveled the globe photographing social movements such as the Landless Workers Movement of Brazil, worker-controlled factories in Argentina, a traditional gift economy in Mali, and the Zapatistas.

What advice would you give to someone who is interested in working with photography for social change or starting a non-profit in this area?

Practice being an ally to those you want to document. That means as much listening as acting. Sometimes, if you haven’t established comfort or consent among all parties involved, it may even mean not taking photos, and that is okay. This especially holds true if you’re documenting people who have been marginalized, victimized, or disenfranchised in any way: the last thing you want to do is propagate a dynamic of exploitation. Do what you can to elevate the voices of those who have been disempowered and learn to look holistically beyond the frame of the camera to see the full story of your subject.

You set up an educational photography program in West Africa in 2007. Can you tell us more?

I had been planning my trip to Mali to document the gift economy when my contact at the school there reached out and asked if I could teach a class on photography while I was in the country. Ecstatic, I recruited photographers Mariette Papic, Nathan Reimer, and Shane Condino to help, and the endeavor quickly grew. I put a call out on Craigslist for cameras and film, and New Yorkers responded, as they do. We ended up bringing 40+ cameras, hundreds of rolls of film, a couple computers, a printer, and a projector over to a grade school in Kati, where we spent a few weeks teaching kids photography. It culminated in an outdoor exhibit of their images, and ostensibly an on-going photo program at the school. We called it “Mali Multi-Media”. I’m super proud of it.

When you’re traveling, what gear do you take with you and why?

If I’m not explicitly on a photo project trip, I like to travel super-streamlined and will usually bring my Fuji X100T, which I’ll put in a Domke wrap and stick in a side-pocket. I love the rangefinder feel with throwback film settings and wifi transfer for ease of posting to social media and the like.

In the field, what are your favorite or go-to settings for easy shooting?

Sunny 16 rule. And always know where your light is coming from.

What has been the most challenging project that you’ve worked on?

I often joke that I’m the laziest photographer in the world — I essentially built a photographic system where everyone else puts in the labor (working slogan: “The Self-Portrait Project: You do it!”). However, SPP is by far the most challenging, frustrating, and gratifying project I have worked on. Years ago I made a deliberate choice to put down the camera, so to speak, and focus on facilitating others in capturing their own portraits. I am a very visual person, and it has been a process to retrain my eye to — rather than compose an image within a camera frame — envision The Self-Portrait Project as a whole as the actual art. And in realizing my vision for SPP, I’ve had to learn all kinds of skills I hadn’t previously had, such as fabrication, graphic design, database administration, programming, etc., which has taken determination and a good dose of humility. I’m not quite at elite autodidact polymath levels yet, but I have added a few more tools to my Swiss Army Knife #MacGyver.

Thinking back on iconic images that have altered the social, political or cultural landscape in just a fraction of a second, do you think that photography still has the power to change the world?

I think powerful pictures will always be powerful. And I am still in awe of photography’s ability to transform thought and emotion — artists as modern-day alchemists. If anything, social media’s ability to quickly amplify images across the globe only increases the potential of photography’s role in social change. I do think that the ubiquitousness of video has created more accountability in the world. Rodney King was a prelude in a way to how the Walter Scott, Philando Castile, and George Floyd videos helped propel the Black Lives Matter protests last summer and to fuel outrage/motivate action over racial injustice in the United States. I know they have had that effect on me. On that note, WITNESS is a non-profit I am quite fond of which is doing fantastic work helping activists around the world create eyewitness videos documenting human rights abuses in order to further change in their communities.

In your experience as a photographer, do you think that photography plays a role in understanding cultural barriers and building better communication? If so, how?

For me, photography is a primary way of expressing the world I see around me, but it is also one of the main vehicles through which I attain a better understanding of the world. There is a reason why I feel compelled to photograph when I travel to a new place. Other Worlds was as much me documenting alternative economies as it was me learning about them. I think anytime you put yourself in a receptive state — listening, meditating, photographing — you make it possible to build a bridge between yourself and that from which you’re receiving.

How do you make a connection with people when photographing them?

There is a concept in Mali called “maaya”, which loosely translates as “humanness”. A common Malian expression explains maaya: “Life is a cord. We make the cord between ourselves, and you have to hold on to it. One should not drop the cord.” When I’m working well, I feel that I’m already connected to the person I want to photograph; it’s just a matter of acknowledging that connection to them.

Do you have any personal mantras which help guide you during the course of your work?

Love is always the appropriate reaction.

As your career has progressed, how has your aesthetic and subjects shifted over time?

The advent of digital photography certainly affected my overall aesthetic. Shooting film is far more meditative for me than shooting digital — there is something almost spiritual to the acts of loading the film, winding between frames, feeling the snap of the mirror; it’s a rite of sorts, and I like to think that my film images reflect this reverential attitude.

Along the same lines, as I embrace technology via my work with SPP, there is a part of me which wants to go the other way, to slow things down. Recently I got my hands on an 8×10 view camera, previously owned by late great photographer Naum Kazhdan, which I can’t wait to start using.

And perhaps because of my work with SPP having enabled tens of thousands of individuals in the creation of their own images — we currently have almost a million portraits in the archive — I feel less of a need to capture people in my own work, and recently have been more compelled to pull back and grab the bigger picture ala street and landscape photography.

What do you suggest to people wanting to improve their skills as a photographer?

Shoot film and develop it yourself. And develop your own photos. I think you learn your lessons more deeply with film than with digital, because the mistakes you make with film come at a higher cost: you’ve invested more time, energy, and money into the process. On the print side, the experience of putting a blank piece of paper in a clear liquid and seeing an image you’ve had in your head for a week emerge from the liquid is unparalleled. It’s alchemical, and it’s addictive.

What’s up next for you?

With regards to The Self-Portrait Project, I’m focused on installing public mirrors which would connect disparate areas and people of the planet to each other. I want to see how our unique system of photography might be used to facilitate more empathy in the world.

As far as personal projects go: years ago I was in Chicago to do a talk on youth philanthropy; as it was my first time there, I took the opportunity to seek out the site of my father’s plane crash. It was located behind what is now a police station, and maintained as an open field, with a solitary apple grove standing in the middle of it. I ate an apple on the spot and brought others back for my grandmother, mom, and sisters. When I find time to do personal projects again, I’d like to do a series focusing on the physical sites of tragedies: their capacity — and by proxy the capacities of those affected by the disasters — for recovery, rebirth, and renewal.

Thank you for sharing with us, Andy!

To view more of Andy’s work, explore his photos on Noun Project, visit his website, and follow him in Instagram. You can learn more about The Self Portrait Project here and follow the latest updates on the project on Instagram.

Interested in joining our community of photographers and contributing to Noun Project? Submit your photos and explore our guide to creating authentic, inclusive images.

Click here to download FREE photo shoot production document templates.

Plan your photo shoots out for the year with our free monthly photo shoot guide.

For more photography tips, check out our blog.

Sign up for our photo newsletter to make sure you never miss out on our photography content.